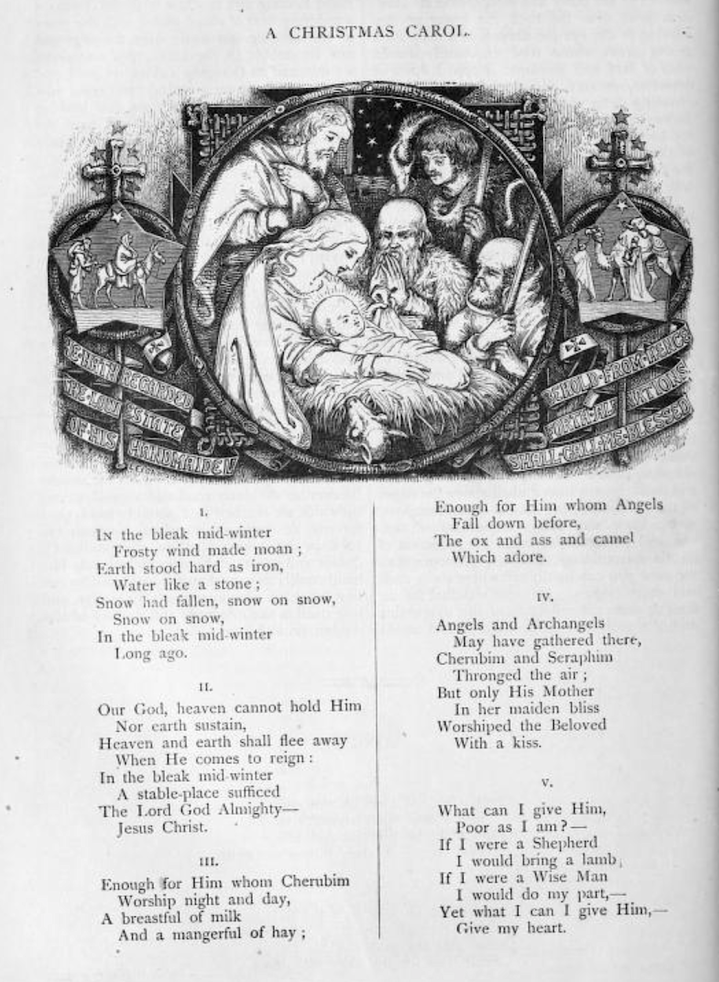

“In the Bleak Midwinter” is one of my favourite Christmas carols. It is, surely, the most beautiful. And it just has to be sung to Holst’s melody, not Drake’s. Yet I’ll concede it’s a peculiar carol, and it’s surprising when one looks at it a little closely that it’s succeeded as it has. It did, in fact, begin life as a poem, rather than a carol–although it was first published under the title “A Christmas Carol”!

I don’t mean the fact that it imagines the Nativity in a snowy winter landscape, rather than in the deserts of Palestine. People often seem to chalk this up to some kind of sentimentalising Victorian ignorance, as if Christina Rossetti, who penned the words, believed such was actually the scene at the birth of Christ. But she was a smarter cookie than you or me, folks–she knew it didn’t snow in Bethlehem.

One of its curious features is its highly irregular meter, and the irregular syllable count in each line. Let’s count:

In the bleak midwinter, frosty wind made moan, (11)

Earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone; (11)

Snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow, (10)

In the bleak midwinter, long ago. (8)

Our God, Heaven cannot hold Him, nor earth sustain; (12)

Heaven and earth shall flee away when He comes to reign. (13)

In the bleak midwinter a stable place sufficed (12)

The Lord God Almighty, Jesus Christ. (9)

Enough for Him, whom cherubim, worship night and day, (13)

A breastful of milk, and a mangerful of hay; (12)

Enough for Him, whom angels fall before, (10)

The ox and ass and camel which adore. (9)

Angels and archangels may have gathered there, (11)

Cherubim and seraphim thronged the air; (10)

But His mother only, in her maiden bliss, (11)

Worshipped the beloved with a kiss. (9)

What can I give Him, poor as I am? (9)

If I were a shepherd, I would bring a lamb; (11)

If I were a Wise Man, I would do my part; (11)

Yet what I can I give Him: give my heart. (10)

The rough pattern is three lines of between ten and twelve syllables each, before a shorter fourth line of eight or nine syllables. This irregularity is hidden somewhat when the carol is sung–the slightly awkward lengthening of “sno-ow o-on snow” and “fa-a-all before”, the contraction of “Heav’n” in the second verse. The prevailing meter is trochaic tetrameter, but this moves around too. Rossetti, being a master, is of course free to break these rules.

For all the variations in meter and syllables though, the most notable is the second stanza. The first three lines run to 12, 13, and 12 syllables–nowhere else do we have three consecutive lines exceeding 10 syllables. When the carol is sung, the start of the second verse (“Our God”) is one of only two places where the rhythm breaks down, “Our” falling on the upbeat before you land on the start of the musical phrase (the other place being the masterfully placed “Yet” at the start of the final line).

So: why expand the syllable count there in the second stanza? It seems to me that it’s a perfect way of mirroring the content of the words there:

Our God, Heaven cannot hold Him, nor earth sustain;

Heaven and earth shall flee away when He comes to reign.

In the bleak midwinter a stable place sufficed

The Lord God Almighty, Jesus Christ.

The first two lines are about the sheer grandeur and greatness of God. Rossetti is doubtless picking up on Solomon’s words at the dedication of the temple in 1 Kings 8:27: “But will God indeed dwell on the earth? behold, the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain thee; how much less this house that I have builded.” Rossetti’s careful choice, among shifting syllables, to have the syllables swell at this point, poetically mirrors God’s greatness. The earth cannot contain him, nor the heaven of heavens–how could Rossetti’s mere line of verse, even as it strains the limits of its syllables?

And yet, incredibly, God chooses to dwell in the temple, and to be contained by a house built by human hands. And we can see here that Rossetti’s choice of scriptural allusion, with the temple lingering between the lines, is made with poetic and theological purpose. The temple is a mere foretaste of the incarnation, when, rather than a grand temple, “a stable place sufficed”; the uncontainable one, “The Lord God Almighty” dwelt–or tabernacled–among us as “Jesus Christ”, somehow, forever, contained in the flesh.