At what stage of Protestant retrieval are we? It is tempting to compare our situation with that facing Catholics in the second half of the nineteenth century. Then they were slowly rediscovering their intellectual tradition, and work on critical editions of medieval scholastics would soon begin. Translations would follow, and then official statements about the value of the whole enterprise, most famously in the encyclical Aeterni Patris and its call for the study of Aquinas. Of course, this is not exactly our situation. We have no magisterium issuing such an encyclical, and there are only a handful of works for which we have a critical edition. But the massive digital availability in some ways compensates for the lack of such editions, and the movement of translation is perhaps stronger than it was in the nineteenth century. It almost feels like an encyclical had been issued.

But the growth of the movement brings with it important discussions, and the one that has been taking place in the last few weeks is crucial. Can we stop at theological retrieval, or should we move on to embrace the social and political thought of our sixteenth and seventeenth century fathers? An article by John Ehrett, somewhat critical of this “expanded retrieval,” led to a podcast discussion at the Davenant Institute and a series of articles as part of a symposium at American Reformer. Part of the discussion is obviously driven by current concerns in American politics, which as an outsider I am not in a position to comment on. But it is a good conversation to be having. We all want to retrieve some things from the past and leave others behind, but there is not much principled reflection on how we make that choice. Does retrieval aim to re-order the hearts and minds of Christians, or also to re-order the society around them? How does retrieval expand our political imagination? Is all such expansion desirable? Are the “factions” in these debates divided over prudential application or also over principle? Is there even such a thing as a set of practical principles that constitute a moral and political orthodoxy (akin to the theological one)? These are some of the relevant questions raised by the article and the discussion around it.

Aterni Patris, to return to that Roman Catholic document, certainly suggested that such a practical orthodoxy exists. It called for a philosophy that would strengthen the path to the true faith, but it was also concerned with the political reality of the post-1789 period. If “a more wholesome doctrine were taught in the universities and high schools,” it would benefit “domestic and civil society” (n. 28). Protestants of all factions can agree on this. Or, to put it in words from the beginning of the encyclical, we can agree that many of our problems can be traced back to “false conclusions concerning divine and human things which originated in the schools of philosophy” (n. 2). A “more wholesome doctrine” must be retrieved not only regarding divine, but also regarding human things.

But while Aeterni Patris confirms the need for such a twofold retrieval, it also presented the social thought of Aquinas in very general terms. The encyclical calls for a recovery of “the teachings of Thomas on the true meaning of liberty,” “on the divine origin of all authority, on laws and their force, on the paternal and just rule of princes, on obedience to the higher powers, on mutual charity one toward another” (n. 29). Given the general nature of this outline, it is perhaps not surprising that very different political projects could emerge among the Thomists in the decades that followed. Some of these projects were more purely critical of modern politics, while others, such as those of Jacques Maritain or Yves Simon, moved towards a critical reconciliation between Thomist philosophy and aspects of this world, such as democracy or religious freedom. In the light of this parting of the ways among the readers of the encyclical, the various forms that the Protestant ressourcement has taken may seem rather unremarkable.

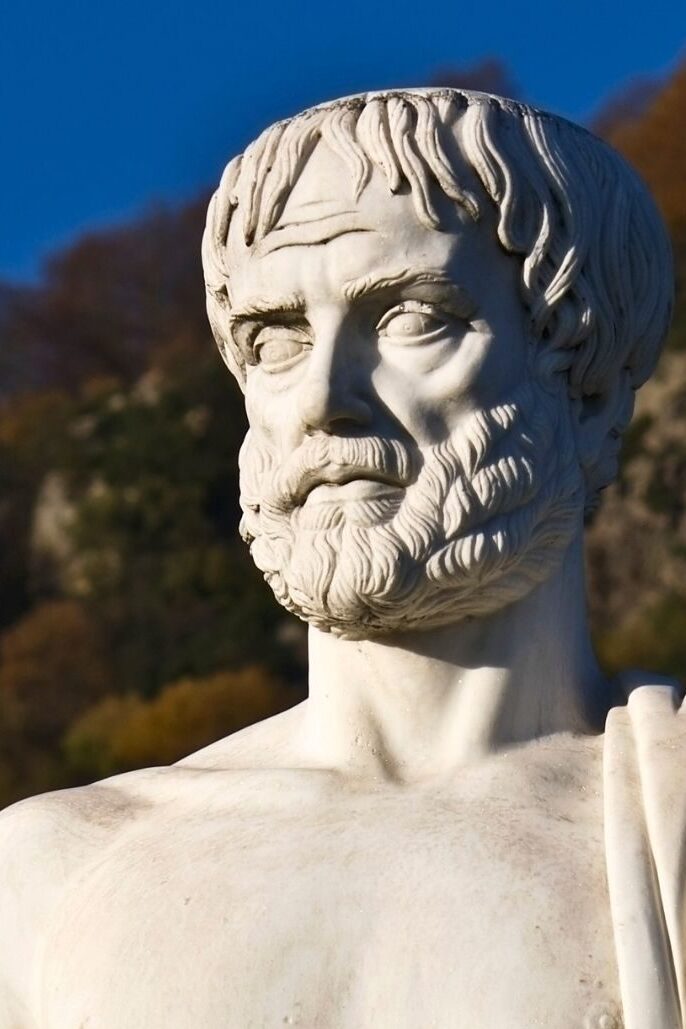

But this analogy is of rather limited value. Our chronological proximity arguably makes a more direct reception of the Protestants more plausible. Politics, moreover, plays a greater role among sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Protestants than in the great thirteenth-century theological systems (there is no thirteenth-century Hooker or Althusius). So perhaps the reception of this political thought can take a more direct route. But how did Reformation era Protestants themselves think of retrieval? How did they think about the links between our theological and our political heritage? Such questions do not lend themselves to hasty answers. It is true that the divine and the human belong together. As Calvin famously writes at the beginning of the Institutes, the knowledge of God and the knowledge of man together constitute the sum of wisdom. But there is also a place for emphasizing the differences between these realms. To do this, it may be instructive to consider Aristotle, whose philosophy was appreciated by both medieval scholastics and classical Protestants.

This is a special case because, unlike other ancient philosophical schools, Aristotle did not claim a unified wisdom that encompassed both divine and human things. Divine things –eternal, unchanging, wonderful– were the object of one kind of wisdom. He dealt with such things in a body of work that included books such as his Physics and Metaphysics. His practical philosophy, on the other hand, he explicitly called a “philosophy of human things.” These things, ethics and politics, were dealt with in another set of works. And Protestant writers in the Early Modern era often dealt with this field of human things recognizing its relative independence. Sometimes, of course, these Protestant philosophers and theologians wrote great systems that emphasized the connection between human and divine things. In Christian Aristotelianism, whether medieval or early modern, the distinction between practical and theoretical knowledge was never as strictly upheld as in Aristotle himself. But Protestants wrote dozens of commentaries on Aristotle’s Ethics, treating it with an independence that would have been familiar to the Greek philosopher. Only one commentary on the Politics begins with knowledge of God and his government of the world as a prerequisite for adequate political knowledge (John Case’s Sphaera Civitatis, perhaps more informed by his opposition to Machiavelli than by his adherence to Aristotle).

As the titles of these Aristotelian works remind us, however, there are also important distinctions within the world of human things. Both ethics and politics deal with social and rational animals in a world of contingency, but they are not the same. Politics deals with the good of men not only as social beings but as citizens. According to Aristotle politics exists, moreover, because not everybody will be open to the kind of rational persuasion presented in the ethics. There is continuity between both disciplines (and between both books), but once we focus on these differences we note that politics is more context dependent than ethics; and Aristotle’s Politics is, of course, more context dependent than his Ethics. This has consequences for the reception of both works. Writing in the mid 1740s, Johann Jakob Brucker stated that “No part of philosophy has been amended, enlarged, and filled up so much by the Peripatetics themselves as the one dealing with political prudence” (Historia critica philosophiae vol 4, 2, p. 778). Ethics and politics may be part of a single course in “philosophy of human things,” but Brucker’s words could in no way be applied to the reception of Aristotle’s moral thought.

Looking at the Protestant commentaries on both Aristotelian works, this contrast stands out very clearly. It is, after all, detectable at the simple level of the number of commentaries. Protestants wrote around 50 commentaries on the Ethics and barely 15 on the Politics. Why? Not because they were less concerned with politics than with ethics. While some authors –Melanchthon, Camerarius, Golius, and a few others– wrote commentaries on both works, it was equally common for an author (such as the influential Franco Burgersdijk) to write a commentary on the Ethics and then a systematic work on politics (a work that would therefore follow Aristotle’s text less closely). Wolfgang Heider, for example, wrote a Philosophiae moralis systema and a Philosophiae politicae systema, but although these almost identical titles suggest that they are twin works, only the former is a commentary on Aristotle. In other words, these Protestant Aristotelians wrote Aristotelian works on politics, but not commentaries on the Politics. They continued to draw profitably from Aristotle’s political thought, but retrieving Aristotelian politics required a much deeper exercise of mediation and adaptation to the contemporary context than retrieving his moral philosophy.

But if moral and political thought are subject to such different forms of reception, there is nothing surprising or objectionable in the fact that political retrieval follows a different trajectory from theological retrieval. Recognizing these differences is, of course, compatible with an enthusiastic commitment to moral and political retrieval. In the case of the Aristotelian tradition, it is indeed practical philosophy that has been particularly vibrant since its rehabilitation in the 1960s and the subsequent resurgence of virtue ethics. But again, Protestant commentaries on Aristotle are instructive on the different forms in which this practical realm relates to Christianity. Commentaries on the Ethics were usually preceded by a preface outlining the relationship between moral philosophy and the Gospel, whereas such preliminary considerations are rarely found in the treatment of the Politics. I would not suggest that any general or binding conclusions follow, but this is how at least one significant body of Protestant literature originally worked: with a sense of the unity of divine and human things, but also of their difference.

Manfred Svensson is Professor of Philosophy at the University of the Andes, Chile. He is the author, most recently, of The Aristotelian Tradition in Early Modern Protestantism (OUP, 2024).

If you found this interesting, check out more from the Davenant Institute…

The End of Protestant Retrieval

John Ehrett on the limits of “expanded retrieval”

Political Prudence as Fuzzy Thinking

Do appeals to “prudence” often just mask fuzzy theology?

Why Protestants Reads Aristotle’s Ethics

Matthew Mason on the enduring appeal of Aristotelian ethics for Protestants.