How should we live faithfully as Christians, with our distinctive beliefs, practices, and values, in an increasingly pluralistic age? In his widely influential work To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World, Christian sociologist of religion James Davison Hunter calls Christians to reject the dominant paradigms of defense, relevance, and withdrawal and instead embrace lives of faithful presence in their various callings and places.[1] Hunter provides an inviting picture of what faithful presence looks like in both theory and practice.

The realities of pluralism and the “cross-pressures”[2] that we all experience as we seek to live faithfully while loving others mean that certain tensions characterize our attempts to be faithfully present. Christians who recognize the inevitability of these tensions are not necessarily unwilling to make hard choices, nor have they succumbed to compromise—accusations that may be raised by those who do not themselves feel the weight of the tensions. Rather, to live in the midst of these tensions means to recognize that we are not God, but serve one who sees the bigger picture and is able both to forgive and to redeem all our failings. According to Hunter,

the call “to be in the world but not of it” is a call to abide in the will and purposes of God in the present world disorder with integrity, and the only way to reach for that integrity is to recognize the tension and to reside within it knowing that failure is inevitable, forgiveness is ever available, and the work of the Holy Spirit to transform and sanctify our efforts is always inscrutably at work.[3]

Christian philosopher James K. A. Smith concurs that living with tension is an inescapable aspect of Christian faithfulness:

The call to follow Christ, the call to desire his kingdom, does not simplify our lives by segregating us in some “pure“ space; to the contrary, the call to bear Christ’s image complicates our lives because it comes to us in the midst of our environments without releasing us from them. The call to discipleship complicates our lives precisely because it introduces a tension that will only be resolved eschatologically.[4]

I want to identify three tensions that are characteristic of Christian faithfulness in the midst of pluralism: affirmation and antithesis, engagement and distinctness, and humility and hope. Christian faithful presence tries to live in the midst of these tensions, rather than accepting easy resolutions of them that result in an abdication of faithfulness.

In the words of James K. A. Smith, “Faithful witness is a precarious dance.”[5] In other words, faithfulness in the midst of pluralism is never a settled thing, but looks different in different times and places and for different individuals, families, schools, and churches. Any step of faithfulness in the present, any attempt to correct the excesses of the previous generation, may itself prove in hindsight to be an overstep in the other direction, itself in need of correction. Yet faithfulness resists the search for settled positions and final solutions. So we cannot avoid the dance, but can only seek to dance more wisely and more faithfully, in full recognition of its precarity. This paper describes some of the steps of the dance.

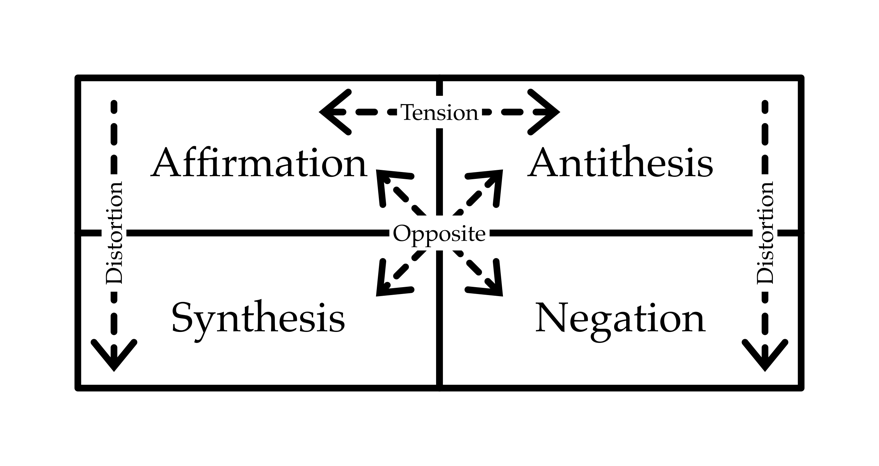

Affirmation and Antithesis (vs. Synthesis or Negation)

First, faithful pluralism is characterized by the tension between affirmation and antithesis.[6] Affirmation involves explicitly recognizing and celebrating whatever is good, true, and beautiful in human cultural activity, regardless of its religious, spiritual, or ideological orientation. For example, a Christian might read a Zen Buddhist haiku as a window into “God’s marvelous creation and the glories inherent in each moment.”[7] Even so, the author of the haiku is a Buddhist, not a Christian, and Zen Buddhism is fundamentally opposed to Christianity.[8] To recognize this is to engage in antithesis, which means not only analyzing the opposition between incompatible worldviews, but also highlighting the alternative interpretation that Christianity offers.

The practice of affirmation rests on the theological concepts of creation and “common grace,” meaning the many good gifts of God that are shared by Christians and non-Christians alike.[9] Common grace includes natural goods, such as rain and sun; relational goods, such as children and friends; and especially cultural goods, such as science, the arts, government, and education. The concept of common grace opens Christians up to affirm the goodness of many aspects of cultural activity, including the efforts of non-Christians. Furthermore, it leads us to see all aspects of human creativity as enabled by God the Creator.

Yet affirmation leads directly and necessarily to antithesis. In almost the same breath as Christians affirm that the world and human culture are good, we must also acknowledge that the world is fallen and humans are sinful. In particular, the Reformed tradition emphasizes the doctrine of “total depravity,” which means not that everything humans do is evil, but rather that the taint of sin touches every aspect of human existence. As Hunter says, “Antithesis is rooted in a recognition of the totality of the fall.”[10] Although it is individuals, not cultures or ideas, who are depraved, the effects of that depravity can be felt in all that humans do. For this reason, many aspects of cultural and intellectual activity—including certain artistic expressions, philosophical assumptions, and political arrangements—are fundamentally at odds with Christianity. So we cannot affirm everything about human culture, but will seek to reveal the antithesis between Christianity and other competing belief systems.

Yet Hunter emphasizes that “antithesis is not simply negational. Subversion is not nihilistic but creative and constructive.”[11] Therefore, antithesis involves not only showing the conflict between Christian and non-Christian worldviews but also developing the Christian worldview as an appealing alternative to other patterns of thought and behavior. In this way, antithesis leads back to affirmation, recognizing much that is praiseworthy in non-Christians’ pursuit of art, scholarship, justice, and other areas of human culture. Similarly, affirmation always leads directly to antithesis: it does not merely recognize the goodness in non-Christians’ cultural activities, but also resituates that goodness in the context of God’s gracious gifts. Thus, these two attitudes cannot exist independently of one another, but each must continually bleed into the other.[12]

Both the interconnectedness of and the enduring tension between affirmation and antithesis can be seen more clearly by means of contrast with two other attitudes that often masquerade as affirmation and antithesis but are in fact perversions of them. These are negation and synthesis. As Hunter explains,

unlike “antithesis” which is constructive opposition, representing a contradiction and resistance but with the possibility of hope, the concept and practice of “negation” have become expressions of nihilism. It offers nothing beyond critique and hostility. It is antagonistic for its own sake. This, it would seem, is contrary to the gospel. “Synthesis” is problematic because it presupposes a blending and an accommodation with that which it opposes. “Affirmation,” by contrast, does not require assimilation with its opposition to validate actions or ideas generated by the opposition of which it approves.[13]

Figure 1 The tension between affirmation and antithesis[14]

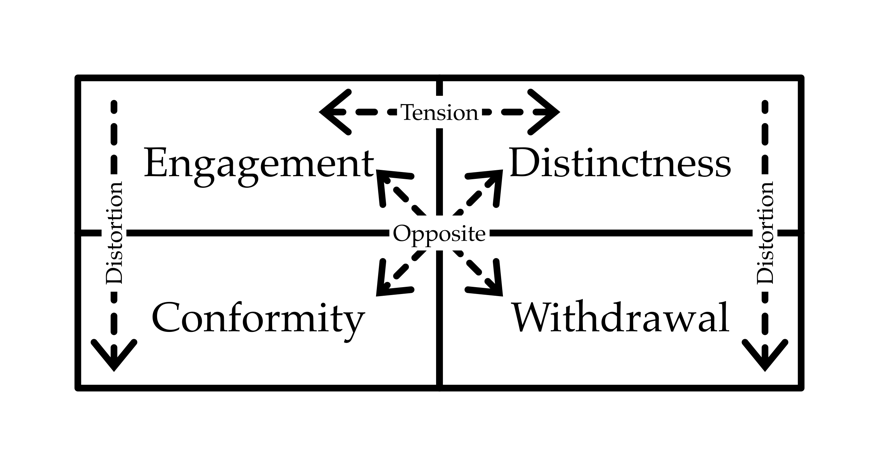

Engagement and Distinctness (vs. Conformity or Withdrawal)

In addition to the tension between affirmation and antithesis, faithful presence also requires living in the tension between engaging the world and remaining distinct from it. In fact, these two tensions depend upon one another: it may be easier to avoid the distortions of engagement and distinctness by keeping in mind the goal of balancing affirmation and antithesis (rather than sliding into either synthesis or negation); at the same time, successfully holding affirmation and antithesis together requires Christians both to engage, and to do so from the fullness of our distinctness as Christians.

Just as we differentiated between affirmation-and-antithesis and synthesis or negation, engagement and distinctness must be distinguished from their distortions. The distortion of engagement, which often masquerades as it but is in fact a perverted form of it, is conformity. This can mean the conformity of Christians to the world, as happens when Christians try to be ‘relevant’ to the world, but find ourselves gradually becoming more like the world. Or it can mean insisting that the world conform to (a particular interpretation of) Christian principles, so that there is no longer a distinct world to engage. On the other hand, the distortion of distinctness is withdrawal, such as that manifested by various forms of Christian separatism. In the same way as affirmation becomes synthesis when it ceases to be balanced with antithesis, and antithesis becomes negation when it ceases to be balanced with affirmation, so too engagement becomes conformity when the engagement no longer comes from a place of distinctness, and distinctness becomes withdrawal when it is no longer oriented toward engagement.

Figure 2 The tension between engagement and distinctness

Christian ethicist Luke Bretherton points out that any given instance of similarity between the church and the world may be a failure to maintain the church’s distinctiveness, but need not necessarily be so: “[The church’s] likeness to its neighbours is not only an issue of idolatry and unfaithfulness. While this is sometimes the case, the church can often be like the world in good and generative ways. It can also be unlike the world in negative and degenerative ways.”[15] Bretherton calls for a “case by case evaluation” rather than a total dismissal of anything that looks too similar to the world, recognizing that “at the level of social practice, we should expect to see both convergence and divergence of practice; that is, the social practices of Christians will not, of themselves, always be distinctive from the practices of non-Christians.”[16] This combination of “both convergence and divergence” results in a tension: “The church is both fashioned out of the world, and hence is like the world, and yet it is fashioned in response to the Word of God, and therefore, is unlike the world.”[17] In consequence, Bretherton encourages us to pursue specificity (i.e., living in specifically Christian ways) rather than distinctness merely for the sake of being different from our non-Christian neighbors.[18] And he reminds us that Christians are pilgrims, in but not of the world, and so will experience “both distance and belonging,” rather than either withdrawal or assimilation.[19]

Like Bretherton, James K. A. Smith recognizes both the difficulty of dwelling in this tension and the importance of doing so well. Referring to the challenges of engaging in Christian formation in the midst of powerful influences from the surrounding culture, he postulates, “it may be the case…that a Christian community that seeks to be a cultural force precisely by being a living example of a new humanity will have to consider abstaining from participation in some cultural practices that others consider normal.”[20] Such abstention might sound like separatism. But the essential difference is not in the actions of abstention and separation themselves, but rather in the purpose to which they point:

[T]he abstention would not be primarily negative or protective: it would be undertaken in order to engage in cultural labor otherwise, to unfold cultural institutions that are ordered by love and aimed at the kingdom, cultural practices that are foretastes of the new creation and that, as such, would themselves function as winsome witness to God’s redemptive love.[21]

Thus, Smith does see a role for cultural engagement, and an important one at that. Even so, he insists that such engagement must be truly distinctively Christian, and this can only happen by means of selectively abstaining from certain practices and norms of the surrounding culture. Yet such abstention does not serve the end of resistance merely for the sake of being different, but rather creates space for forming alternative, more genuinely Christian practices and habits.

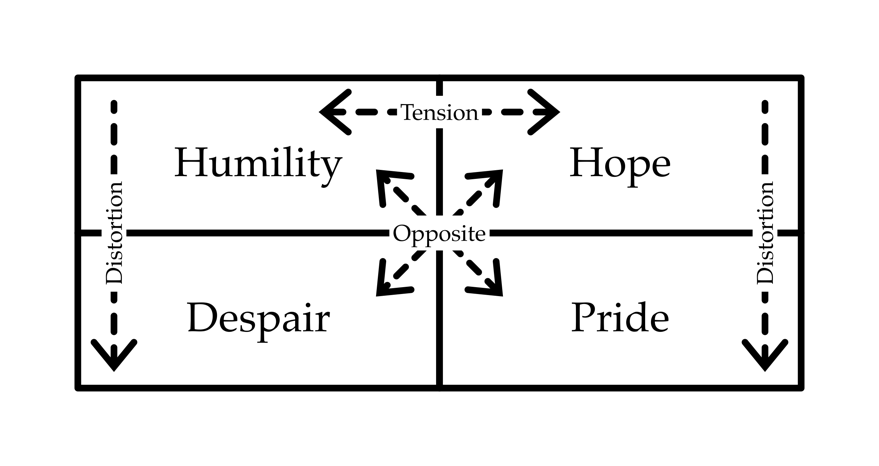

Humility and Hope (vs. Pride or Despair)

Though the previous two tensions are perhaps the most obvious when considering American Christians’ interactions with pluralism, they in fact rest on an even more basic tension: that between humility and hope. Matthew Kaemingk describes Dutch Reformed theologian and statesman Abraham Kuyper’s approach to life in the midst of pluralism as “humble yet hopeful,”[22] and this description must characterize all Christians who seek to live in the world with faithful presence. Christians are humble because we recognize that living together in the midst of deep differences is really, really hard, and that we will often fail to do so well. Indeed, Christians must remain humble regarding both our own ability to exhibit affirmation-and-antithesis and engagement-and-distinctness, and the outcome of our efforts to do so, which ultimately rests on factors outside our control. Yet we remain hopeful about the possibility of faithful living in the context of deep pluralism, even if it ends up being messier and on a smaller scale than we might desire.

Once again, humility and hope are each subject to distortions when they cease to be held in tension with one another. The distortion of hope is pride, whereby we forget the depth of the challenges of pluralistic living and assume that we are capable of achieving our goals easily and straightforwardly. On the other hand, when the challenges loom so large that they overshadow any possibility of hope, we abandon humility for despair.

Figure 3 The tension between humility and hope

Kaemingk finds both humility and hope expressed in Dutch Reformed theologian Klass Schilder’s reflections on the suffering and crucifixion of Christ. When the soldiers come to arrest Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane, his disciple Peter, seeking to defend his teacher, draws a sword and cuts off the ear of a slave. Far from engaging in self-defense or even endorsing it, Jesus instead rebukes Peter and heals the slave. Following Schilder, Kaemingk sees this not as a moment of weakness but as a window into the nature of Christ’s kingly power: “Christ’s sovereign healing and power will not always take the cosmic and revolutionary scale the world so often expects or demands. The royal power of Christ’s sovereign is often limited, humble, partial, and seemingly small.”[23] From this moment of small, humble healing, Kaemingk turns to the crucifixion itself, and specifically to Jesus’ nakedness on the cross. He explains that, though respectable Christians may be scandalized by the exposure and vulnerability of one whom they revere as savior and king, his disrobing is in fact their own doing. “For in his disrobing we are fully exposed. We see ourselves for who we truly are—violent, fearful, and selfish. Beholding the naked king, we see our true nature in all its nakedness. Our pretentions of love, tolerance, and peace are laid bare.”[24] Yet this is not the end of the matter.

While Schilder’s view of human nature is dark indeed, he does not leave his readers naked and shivering in a state of total despair. In fact, it is here at the lowest point of the meditation that Schilder points to a deep hope. This hope is grounded—not in the goodness of humanity—but in the goodness of God.[25]

This brings us to a crucial point. For Christians, the tension between humility and hope—much like the previous two tensions—is resolved with reference to the divine. Christians are humble because of how weak and sinful humans are, yet they can be hopeful because God’s power is not limited by human weakness or sinfulness. In particular, the hope that justifies both patient engagement and active waiting is eschatological, tied to the promised return of Christ to rule as king. According to James K. A. Smith, “To worship Christ the King is to be a people with a kingdom-oriented stance, which will sometimes look aloof and will at other times pitch us into the fray. The posture of heavenly citizenship is a posture of uplift, tethered by hope to a coming King.”[26] This eschatological vision counteracts tendencies toward both pride and despair: “A teleology that is at once an eschatology will be countercultural to every political pretension that assumes either a Whiggish confidence in human ingenuity and progress or alarmist counsels of despair.”[27] It is, then, this uniquely Christian hope that equips us to live well with those who reject that very hope.

Emily G. Wenneborg has a Ph.D. in Philosophy of Education and Religious Studies from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She is interested in the challenges and possibilities of Christian formation in the context of late modernity.

James Davison Hunter, To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). ↑

Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2007); see also James K. A. Smith, How (Not) to Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2014). ↑

- Hunter, To Change the World, 183–84. ↑

- James K. A. Smith, Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2017), 192. ↑

Smith, Awaiting the King, xiii. ↑

Those who are familiar with the Neo-Kuyperian stream in Reformed Christianity may recognize similarities between this tension and the widely-used distinction between structure and direction. Structure refers to the creational reality that can never be completely destroyed, while direction refers to the orientation of any particular created thing either toward or away from God; thus, in my terminology, structure is subject to affirmation by Christians while direction must be treated with antithesis. Although this distinction can help us to frame our questions in more helpful ways, sometimes it does too much work, resulting in trite answers rather than genuine wrestling with the tensions. For this reason, I prefer the terms affirmation and antithesis, which describe the attitudes to be taken by Christians rather than the attributes of created things. For more on the Neo-Kuyperian use of the structure-direction distinction, see Albert M. Wolters, Creation Regained: Biblical Basics for a Reformational Worldview (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1985), as well as James K. A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2009), 122, and Smith, Awaiting the King, 218. ↑

- James W. Sire, Naming the Elephant: Worldview as a Concept, 2nd ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015), 174. ↑

- Sire, Naming the Elephant, 172. ↑

Common grace is distinguished from special or saving grace, which belongs to Christians alone. See David Koyzis, Political Visions and Illusions: A Survey and Christian Critique of Contemporary Ideologies, 2nd ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2019), 235n36. For a discussion and critique of the language of common grace in Reformed Christian circles, see Smith, Awaiting the King, 122–24. ↑

- Hunter, To Change the World, 234. ↑

Hunter, To Change the World, 235. ↑

In Hunter’s words, affirmation and antithesis are two movements in a single dialectic. See Hunter, To Change the World, 231–36. ↑

Hunter, To Change the World, 332n7. ↑

Figures courtesy of Luke Herche. Used by permission. ↑

Luke Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness: Christian Witness amid Moral Diversity (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006), 106. ↑

Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 107; similarly, Reformed Christian teacher educator David I. Smith points out that the story within which Christian educators live matters more than the distinctiveness of the practices in which they engage. See Smith, On Christian Teaching: Practicing Faith in the Classroom (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), 129–30. ↑

- Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 108. ↑

Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 109–10. ↑

Bretherton, Hospitality as Holiness, 111–12. ↑

Smith, Desiring the Kingdom, 209 (emphasis original). ↑

- Smith, Desiring the Kingdom, 210. ↑

Matthew Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), 155. ↑

Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear, 175. ↑

Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear, 178. ↑

Kaemingk, Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear, 178. ↑

Smith, Awaiting the Kingdom, xiv. ↑

Smith, Awaiting the Kingdom, 11. ↑