INTRODUCTION

If one were to ask the average Western Christian to divide church history into its major stages, they would likely demarcate the patristic, medieval, Reformation, and modern eras. But what is the logic behind each era? What makes each different from the other, and what explains the transition from one to the next? And if one were to uncover the logic behind the Church’s past, would this help us understand our current moment—and perhaps even discern our future?

In this essay, I would like to suggest that such a logic does exist and that the Church’s development follows the basic pattern of other living or institutional organisms. To do this, I will bring together the literary insights of Louise Cowan and the historical insights of church historians and show how they cohere with one another. Cowan has explained the logic and coherence of the four classical literary genres by showing their interrelated, cyclical nature. Church historians, meanwhile, have noted that certain biblical books have shaped the Church’s four major eras. When their respective insights are brought together, we can see that Cowan’s description of the development of the four literary genres coincides with the defining biblical books of the four eras of the Church. If this is correct, this would allow us to understand, not only where the Church has been, but also where it is in the present, and (possibly) what lies in its future.

CREATION’S FOUR-PART CYCLE

The world is full of cycles. The day begins with morning, progresses to midday, slips into evening, and then turns into night. The moon waxes, becomes full, wanes, and then disappears into a new moon. The year begins with spring, reaches its high point in summer, slips into fall, and ends with winter. Even the human life cycle follows the same course: we begin as children, grow into adults, enter into our senior years, and finally die. Each of these daily, monthly, yearly, and lifetime cycles has four parts which follow the same basic pattern: each cycle begins with birth, progresses to fullness, falls into decay, and ends with death. This is the predictable—and necessary—course that all organisms follow, even the non-celestial or biological. For example, civil structures such as institutions, corporations, and nations follow this same four-part cycle. However long they may last or however many variables they may include, they all begin, peak, decay, and eventually perish. In summary, and to borrow from Plato and Aristotle, anything that is “becoming”—as opposed to “being”—will follow this cycle, simply because the phenomenological world is always changing. As will become clear throughout this essay, I am suggesting that the Church—an institutional organism of sorts—is following this same four-part cycle.

A LITERARY ANALYSIS OF THE FOUR GENRES

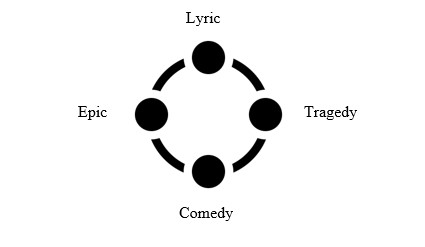

In her edited volume on classical comedy, literary critic Louise Cowan provides a graphic that arranges the four classical literary genres along a wheel.[1] The image that she provides is too detailed for our purposes here, so I produce only a basic model:

The wheel runs clockwise, beginning with epic on the left side (nine o’clock) and ending with comedy at the bottom (six o’clock), at which point the cycle begins again.[2] As for the genres, epic is about new beginnings: it has a hero who defeats the villain and establishes order; epic’s emblem is a new city. Lyric is about the love shared between lover and beloved, especially in a garden: it knows no time and has no plot, but rather celebrates the eternal now of the lovers’ embrace; lyric’s emblem is a kiss. Tragedy is about the calamitous fall of a nobleman: it begins high and ends low, and the destruction is swift and irreversible; tragedy’s emblem is a funeral. Comedy is about the fortuitous rise of a common man: it begins low and ends high and has the ability to provide hope in the midst of darkness because of its transformative vision of how things could be, should be, or even will be; comedy’s emblem is a wedding feast. The point of the wheel is to demonstrate visually the internal movement of the four genres. Taken together, the four genres reflect the four basic gestures that humans can create with literature.

Part of the genius of Cowan’s wheel is that it closely follows the four-part cycles that we noted above: epic corresponds to morning, waxing moon, spring, and childhood; lyric to midday, full moon, summer, and adulthood; tragedy to evening, waning moon, fall, and seniorhood; and comedy to night, new moon, winter, and death. Cowan’s arrangement of the four literary genres is not arbitrary, but rather reflects the natural cycle of life: creation’s four-part cycle is reflected in the four literary genres, and it may even be the explanation of their origin.[3] Also important to notice is that each stage builds on its predecessor(s) and prepares the way for its successor(s). Epic can exist only if there is a previous upward momentum that impels the characters to a new conquest and prepares an ordered place where lovers can rest. Lyric can exist only if there is an ordered city where lovers can embrace one another. This embrace then sets the stage for a calamitous fall. Tragedy can exist only if there is a height from which to fall, preparing the way for endurance during difficult times. Comedy can exist only if the tragic fall has already occurred and provides the momentum for future conquest. So much for Cowan and cycles; now it is time to look at the development of Church history according to its defining books.

IMPORTANT BIBLICAL BOOKS THROUGHOUT CHURCH HISTORY

Church historians have argued that three biblical books have played a significant role in shaping church history’s three major ages: Genesis—especially the opening chapters—was influential during the patristic era, Song of Solomon during the medieval era, and Romans—again, especially the opening chapters—during the Reformation era.[4] Regarding the importance of Genesis in the early church, Andrew Louth notes the following:

The early chapters of Genesis had arguably a greater influence on the development of Christian theology than did any other part of the Old Testament. In these early chapters the Fathers have set out the fundamental patterns of Christian theology. […] One of the most popular genres of scriptural commentary among the Fathers was commentary on the six days of creation, the Hexaemeron.[5]

Epic corresponds to morning, lyric to midday, tragedy to evening, and comedy to night.

As for the importance of Song of Solomon in the Middle Ages, Ronald Murphy writes that “More ‘commentaries’ were written about the Song in the Middle Ages than about any other book in the OT; from the 12th century alone we have some thirty works.”[6] According to E. Ann Matter, between the 6th-15th centuries, nearly one hundred commentaries on the Song of Solomon have survived.[7]

As for the importance of Romans in the Reformation era, Gwenfair Adams writes that, “During the sixteenth century, as far as we can tell, there were more commentaries written on Romans than on any other book of the Bible; from 1500 to 1650 there are at least seventy. In many ways, the Reformation hinges on Romans.”[8]

In fact, Gerald Bray, in his influential work on biblical interpretation throughout church history, used Genesis 1, the Song of Solomon, and Romans to illustrate hermeneutical practice during the patristic, medieval, and Reformation eras, respectively.[9]

THE OVERLAP BETWEEN LITERARY GENRES AND IMPORTANT BIBLICAL BOOKS

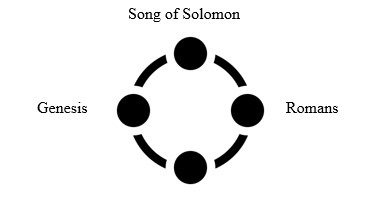

The significance of the findings so far is that Genesis (and certainly its opening chapters), Song of Solomon, and Romans (certainly its opening chapters) overlap precisely with the first three parts of Cowan’s genre wheel: they occur in the correct order and correspond to the correct literary genre. Thus, the opening chapters of Genesis are epic, Song of Solomon is lyric, and the opening chapters of Romans are tragic. This is the logic of church history that I referred to above: the Church has progressed, and still is progressing, through the same basic cycle that other organisms do. Summarizing the argument thus far, this is what the wheel looks like:

We should here consider the overlap between Genesis, Song of Solomon, and Romans with respect to epic, lyric, and tragedy. The patristic era focused on the opening chapters of Genesis—and all the other portions that speak of “ultimate” beginnings, such as John 1, Ephesians 1, Colossians 1, Hebrews 1—because they were living in an age of new beginnings. They overcame the darkness of pagan Rome with the light of the Gospel. It was an age marked by apologists, (victorious) martyrs, expansion into new lands, and the first—and most important—ecumenical councils of the Church. The center of patristic theology was arguably the Father’s victory over evil through the Son, which is found in the texts mentioned above.

Once the new (heavenly) city of the Church had been established, the Church’s focus shifted to God’s eternal love for his bride. This was the task of the medieval church, and attention naturally fell on the Song of Solomon. Their inner focus was directed upward, as they saw themselves as the one embraced by their lover. It was an age marked by high-ceilinged cathedrals, Gregorian chant, and mystics. The center of medieval theology was arguably Song of Solomon 1:2a: “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth!” (ESV).

The opening chapters of Genesis are epic, Song of Solomon is lyric, and the opening chapters of Romans are tragic.

However, the Church came to realize that its purity can only be found at the beginning and end of history, and that during the intermediate period, sin makes us unworthy to be found in Christ’s arms. Thus, the Church had to address our tragic plight and acknowledge our complete unworthiness to be embraced by God. We are not God’s intimate lover, but rather unfaithful spiritual whores who desperately need the unmerited grace of God. This is why the opening chapters of Romans were so important to the Church during the Reformation. It was an age marked by the doctrine of total depravity, predestination, and disdain for the flesh. The center of Reformation theology was arguably Romans 3:9b: “None is righteous, no, not one.”

COMEDY AND THE BIBLE

This brings us to the modern era. If the argument has been correct this far, then we should expect a comedic book (or a portion of it) to shape the next era of church history. First, we must discuss the classical genre of comedy, and then discern whether any biblical books fit into its category.

Classical Comedy

As Cowan has noted, defining the characteristics of comedy is no easy task: “Far more than other genres, comedy invites a skeptical attitude toward any effort to isolate out of its multiplicity a single principle of classification.”[10] Since comedy is “the least exclusive of all literary forms,” the defining marks of comedy are not found in structural or thematic constants but rather in its vision.[11] Cowan argues that Dante is the supreme comedian, and thus his tripartite vision of hell, purgatory, and heaven correspond to the three basic kinds of comedy: infernal comedy, dark and based on justice; purgatorial comedy, pathetic and based on mercy; and paradisal comedy, joyful and based on grace and forgiveness.[12] Other important elements of classical comedy are its power of transformation, its enabling of endurance, and its affirmation of human life, especially through its emblematic sign: a wedding feast. In short, comedy “is a correlative for the hope—and then, finally, one realizes, the experience—of being loved.”[13]

Comedy in the Bible

Regarding specific examples of comedy in the Bible, Louise Cowan and Daniel Russ offer many examples, only some of which can be mentioned here. Cowan states that biblical infernal comedy—“less the world of sin than of abomination”—is occasionally found in the Old Testament, such as in the stories of Sodom and Gomorrah, the false prophets in Pharaoh’s court, Jezebel, and the Tower of Babel, but that its use is limited.[14] She broadly refers to the Old Testament as purgatorial comedy, but without providing examples.[15] Russ, on the other hand, provides several, such as the stories about Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob, Joseph, and others.[16] Interestingly, they do not highlight any examples of paradisal comedy.

What so many of these stories have in common is the ability of the spoken word to overcome the evil forces of chaos and death.[17] That is, God gives promises to his people that provide them with a new way of viewing reality, which in turn relativizes their present suffering and hardships such that they are no longer ultimate, but penultimate. They believe that God’s creative word has the final say, and this is what transforms their vision and allows them to persevere (joyfully) in their pilgrimage. Transformation, endurance, and weddings (or reunions) are constant themes throughout these biblical comedic stories.[18] Many more examples from the Bible could be given, but these illustrate that many of the micro-stories from the Bible are comedic and thus possible candidates for the Church’s next influential text or book.

However, it is not just the Bible’s micro-stories that are comedic, but rather its overall macro-story. Daniel Russ argues that the Scriptures “may be seen to constitute the fullest achievement of [comedy] in Western literature.”[19] In fact, he states that the “archetypal comic plot—order to chaos to order—is the form of the scriptural canon.”[20] He argues that, while Genesis contains the seeds of this comic plot, it is only completed in the eschaton: “And because this God is from beginning to end a covenant maker, betrothing himself to his people, his world will end in comedy: that marriage-feast that characterizes a ‘komos.’”[21]

In short, if the ultimate gesture of Scripture is comedic, and if the seeds of biblical comedy only find their fulfillment in God’s reunion with his people in the marriage feast, then the biblical book most likely to shape the Church during its next era is the one which is the most transformative, provides the most endurance, ends in a wedding feast, and makes real the “hope of being loved.”

REVELATION AS THE CHURCH’S NEXT DEFINING BOOK

The biblical book that best fits this description is the book of Revelation, especially its closing chapters. This is not solely my opinion, but was also that of Eugene Peterson, whose “hunch” from nearly thirty years ago coincides remarkably well with the argument presented thus far. His comments deserve to be quoted in full:

Certain times pull particular books of the Bible into prominence. Augustine, looking for the ways in which the city of God took shape in the rubble of a wrecked and decadent Roman Empire, used Genesis for his text. In the exuberant eroticism of the twelfth century, Bernard fastened on the Song of Songs as a means of praying and living into mature love. Luther, searching for the simple clarity of gospel in the garage-sale clutter of baroque religion, hit on Romans and made it the book of the Reformation. As the twentieth century moves into its final decade, the last book of the Bible, the Revelation, has my vote as the definitive biblical book for our times.[22]

However, there is an important obstacle to overcome in affirming Revelation as a comedic book: most consider it an apocalypse. In what follows, I would like to argue that comedy and apocalypse are not mutually exclusive genres, but rather that the latter is a subset of the former. In other words, I think that Revelation can simultaneously be apocalyptic and comedic.[23]

Just as apocalypse is written for people in crisis in order to exhort and/or console them, so too is comedy written for people who need to endure through pain, trial, and persecution.

First, and to be more precise, there is a consensus amongst biblical scholars that Revelation is best interpreted within the epistolary, prophetic, and apocalyptic genres, with the last being the most predominant.[24] What exactly is the apocalyptic genre? J. J. Collins’ description has become standard:

‘Apocalypse’ is a genre of revelatory literature with a narrative framework, in which a revelation is mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, disclosing a transcendent reality which is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation, and spatial, insofar as it involves another, supernatural world.[25]

However, as other scholars have pointed out, while Collins may have described accurately the form of apocalypse, he has not said anything about its purpose or function. Thus, in order to supplement Collins’ description, David Hellholm writes the following: “I would be willing to accept [Collins’ description], provided the following addition on the same level of abstraction: ‘intended for a group in crisis with the purpose of exhortation and/or consolation by means of divine authority.’”[26]

Thus, combining the two descriptions given to us by Collins and Hellholm, in addition to containing divine–human exchange, apocalypse includes the following three key elements: 1) it provides a new and transcendent reality, 2) it provides a vision of ultimate salvation, and 3) it is written for people in crisis in order to exhort and/or console them.

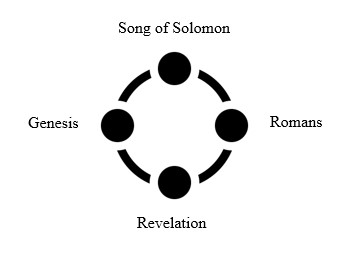

As can be seen, the overlap between apocalypse and comedy is considerable. Just as apocalypse provides a new and transcendent reality, so too does comedy through its imaginative world. Just as apocalypse provides a vision of ultimate salvation, so too does comedy though its climax in the wedding feast. Just as apocalypse is written for people in crisis in order to exhort and/or console them, so too is comedy written for people who need to endure through pain, trial, and persecution. Both genres are written during dark days but with the hope that light and goodness will irrupt in the future (epic) and usher in a new golden age of peace and prosperity (lyric). In other words, if the four classical literary genres of epic, lyric, tragedy, and comedy comprise the totality of the human experience, then apocalypse is best seen as a subset of one of them: comedy. An apocalypse may contain infernal, purgatorial, and/or paradisal comedic elements—and Revelation seems to contain all three of them—but comedy it remains.[27] We can now complete the wheel, which takes the following form:

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE CHURCH

If the basic argument of this paper has been correct, then the Church should take the comedic vision of Revelation very seriously. If it does so, I think it will find an incredibly powerful resource with which to engage our current world.

Comedy is imaginative. What better way to engage with—and confront—a modern world obsessed with images than with the comedic ones of Revelation? Comedy is transformative and redemptive. Instead of a sinner, comedy sees a saint; instead of a pauper, a prince; instead of a whore, a virginal bride. Western culture is crying out for transformation and has completely lost itself in the process. What better way to engage with a lost and broken world than with the transformative and redemptive image of New Jerusalem? Comedy is about hope. It gives a vision that is so glorious and attractive that it is able to give strength and perseverance to those who are suffering and being persecuted. More specifically, comedy is the hope of being loved, especially when one knows that they are unlovable. Is not the modern world obsessed with love and acceptance and yet completely incapable of finding either of them? The only one who truly can fulfill our hope of being loved is God himself, and this message is present profoundly in the great wedding feast in Revelation.

With all of this focus on Revelation, it is important to remember what was said at the beginning of the essay about the relationship between the four literary genres: each stage builds on the previous one (or ones) and prepares the way for the succeeding one (or ones). Thus, Revelation cannot become the Church’s focus in isolation from other books of the canon but rather must take a primus inter pares role—a first among equals. This is simply due to the nature of the moment that the Church finds itself in: in the past the first among equals has been epic Genesis, lyric Song of Solomon, and tragic Romans. For the present, it is comedic Revelation’s turn. Having matured over the past 2,000 years, the Church should now bring all of its rich theological resources to Revelation, interpret it with the benefit of such a rich harvest, and apply it in the Church’s mission to the world.

Having said this, however, I would like to suggest in conclusion that the Church needs to consider seriously the tone in which it presents the Gospel to the world. That is, without changing the message, we may need to change its presentation. To use a musical illustration: since the Reformation, the Church has learned very well the importance of playing the Gospel song in a minor key: sin, wrath, judgment, condemnation. However, as many preachers have discovered in recent years, the effectiveness of preaching a steady diet of tragic messages from Romans is not what it once was. The default response of church leaders is often a defensive one in which we blame our listeners and charge them with apathy. This may be true, but perhaps there is another explanation. Perhaps the Church has already assimilated the tragic teachings of the Reformation and has matured enough to progress to the next stage of growth (just as it did with Genesis and the Song of Solomon). Perhaps we need to change our tone, or at least supplement it with the comedic major key: redemption, joy, grace, life.

Perhaps the Church has assimilated the tragic teachings of the Reformation and matured enough to change to a major key: redemption, joy, grace, life.

Finally, I think that comedy presents a vision which leads the Church toward its greatest need in her current moment: ecumenism. To illustrate the point, let us liken the history of the Church—at least in the West—to a marriage. The marriage began in the early Church, and it quickly led to the honeymoon phase of the Church in the Middle Ages. However, what we found out there was that our bliss was a naïve one, and we fought. This was what the Reformation was about: we realized that we were corrupt from within and decided to split up into our several groups. This was our great divorce. But as time has progressed, we have begun to see the greatness of our own faults and realize how awful it is living apart. So now, fully aware of our own faults as well as those of others, we are beginning to see that it is better to live together than apart. What is needed to bring us back together is a comedic vision of the restorative grace of God. What we need is to renew our vows—together. This is just the kind of vision that Revelation provides us.

CONCLUSION

The remarkable correspondence between Louise Cowan’s literary genre wheel and the conclusions of church historians about church history’s definitive biblical books has led us to the conclusion that there is a logical—and, once we see it, predictable—development to church history. The correspondence has been so complete that it has encouraged me to hazard the prediction that the next defining biblical book for the Church will be Revelation, especially its closing chapters. Therefore, the Church should take very seriously its comedic outlook, which is pressing toward the epic irruption of God’s kingdom and his final lyrical shalom in the garden-city of the New Jerusalem, “prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (Rev 21:2 ESV). This will be the end of the cycle, and it will not repeat again, for sin and death and hell will forever be defeated.

The author of Ecclesiastes reminds us that “for everything there is a season” (Eccl. 3:1 ESV). This is true for the Church as well. In past times, the Church has lived through seasons of epic, lyric, and tragedy. Now, it is time for comedy.[28]

Andrew Messmer (Ph.D., Evangelische Theologische Faculteit) is Academic Dean of Seville Theological Seminary (Spain); Associated Professor at the International Faculty of Theology IBSTE (Spain); Affiliated Researcher at Evangelical Theological Faculty (Belgium); and editor of the World Evangelical Alliance’s Spanish journal Revista Evangélica de Teología. He has written and edited books and articles in Spanish and English. His Spanish page is www.casareinayvalera.com, where he writes about all things related to Christianity. He is married and has five children.

[1] Louise Cowan, “Introduction: The Comic Terrain” in The Terrain of Comedy, ed. Louise Cowan (Dallas: The Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, 1984), 9.

[2] For the purposes of this article, I have explained the wheel slightly differently than Cowan. She began with lyric and ended with epic, whereas I begin with epic and end with comedy (although gesturing toward epic and lyric).

[3] As Cowan says in her Preface, “it seems that genre patterns are patterns in reality which the poet apprehends and then imitates in language.” Cowan, Terrain of Comedy, vii.

[4] Since at least the fourth century, the Psalms and Gospels have played a particularly important role in church liturgy and theology as well, but their influence has been steady and even-handed and has not shaped an era as the other books have.

[5] Genesis 1–11, ed. Andrew Louth, in the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2001), xxxix. Later Louth implies the importance of the opening chapters of Genesis by writing: “After the first three chapters of Genesis, the seam of patristic comment becomes much thinner.” Louth, Genesis 1-11, li.

[6] Ronald E. Murphy, “Patristic and Medieval Exegesis — Help or Hindrance?” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 43, no. 4 (October 1981), 514.

[7] E. Ann Matter, The Voice of My Beloved: The Song of Songs in Western Medieval Christianity (New York: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990), 3. Ann Astell’s comments are also very revealing. Speaking on 12th cent. reflection on the Song of Solomon, she writes: “The voluminous Christian commentary tradition, which stems from Hippolytus and Origen in the early third century, temporarily exhausted itself in the ninth century, only to experience a new flowering during the twelfth-century renaissance. At that time, Anselm of Laon, Bruno of Segni, Bernard of Clairvaux, Rupert of Deutz, Honorious of Autun, Philip of Harveng, Gilbert de la Porree, William of St. Thierry, Gilbert of Hoyland, John of Ford, Thomas the Cistercian, and Alain de Lille all produced expositiones of the Song, the sheer bulk of writings attesting to the peculiar fascination the Song of Songs had for the medieval psyche” (The Song of Songs in the Middle Ages (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990), 8–9).

[8] Romans 1–8, ed. Gwenfair Adams, in Reformation Commentary on Scripture (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2019), xli.

[9] Gerald Bray, Biblical Interpretation: Past & Present (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 12, 115-128, 159-164, 212-220.

[10] Cowan, “Introduction”, 1.

[11] Cowan, “Introduction”, 2, 4.

[12] Cowan, “Introduction”, 10–14.

[13] Cowan, “Introduction”, 15–17.

[14] Cowan, “Introduction”, 12.

[15] Cowan, “Introduction”, 13.

[16] Daniel Russ, “The Bible as Genesis of Comedy,” in Terrain of Comedy, 48–53; cf. 42–43. Russ does not explicitly refer to these stories as purgatorial comedy, but based on Cowan’s affirmation that the authors form a “school of criticism,” it is safe to presuppose his broad agreement with Cowan on this point (vii).

[17] Russ, “The Bible as Genesis of Comedy” 46.

[18] Perhaps this is why the story of the prodigal son (Lk. 15:11–24) has been so popular lately: it is fundamentally comical.

[19] Russ, “The Bible as Genesis of Comedy,” 41.

[20] Russ, “The Bible as Genesis of Comedy,” 43.

[21] Russ, “The Bible as Genesis of Comedy,” 59. Komos is Greek for “a joyous meal or banquet.”

[22] Eugene Peterson, Under the Unpredictable Plant: An Exploration in Vocational Holiness (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1992), 144-145. Without the benefit of the research and categories presented in this essay, the accuracy and fittingness of Peterson’s “vote” is simply astonishing.

[23] I should add, however, that it is debatable if “apocalyptic” is the most suitable genre for Revelation, or if it is even a distinct genre that can be distinguished from prophecy. Additionally, Aristotle was the one who taxonomized genres for the West, and he never mentioned “apocalyptic”, only comedy. For more doubts on Revelation being “apocalyptic”, cf. Frederick Mazzaferri, The Genre of the Book of Revelation from a Source-Critical Perspective (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1989), 382–383; Richard Bauckham, The Theology of the Book of Revelation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 5–6, 9 (somewhat ambiguous).

[24] M.G. Michael, “The Genre of the Apocalypse: What are they saying now?” Bulletin of Biblical Studies 18 (July-December 1999): 115–126.

[25] J.J. Collins “Introduction: Towards the Morphology of a Genre,” Semeia 14 (1979), 9.

[26] Quoted in Michael, “Genre of the Apocalypse,” 124 (italics original).

[27] Infernal comedy can be seen in the overthrow of Babylon, purgatorial comedy in the Church’s endurance throughout the trial, and paradisal comedy in the wedding feast.

[28] I would like to thank Warren Gage for inspiring and equipping me to write this essay.