Today is an important day.

No, not because of that.

Today is an important day because it marks a half-century of Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, released on this day in 1975: one of the greatest albums ever recorded and probably my personal favorite. (I wrote about it a little here.) To celebrate, I want to talk briefly about a couple of internal allusions on the album.

It is well known that Dylan is a great alluder to other people’s words. People like Scott Warmuth, Michael Gray, and the classicist Richard Thomas have documented this beyond all doubt.

I also think that he is a great alluder to himself. I’ve tweeted about this occasionally, but I don’t think I’ve written about it here. So, first, one from Blood on the Tracks looking backward, and then one from later on looking back to Blood on the Tracks.

In “Idiot Wind,” Dylan sings:

It was gravity which pulled us down and destiny which broke us apart

You tamed the lion in my cage but it just wasn’t enough to change my heart

Now everything’s a little upside down, as a matter of fact the wheels have stopped

“[T]he wheels have stopped”: It sounds like he’s talking about about a truck rolling down the highway (or a train rolling down the tracks) and getting stuck. But I don’t think he is; “wheels” is plural for singular, as the next two lines clarify:

What’s good is bad, what’s bad is good, you’ll find out when you reach the top

You’re on the bottom

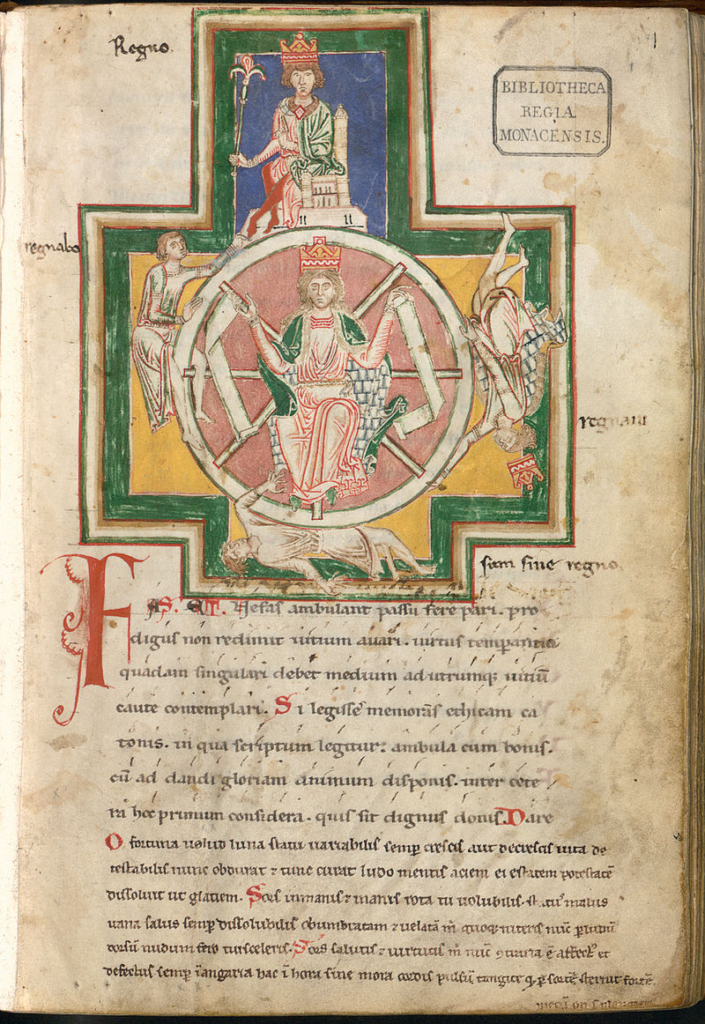

What he’s really referring to, that is, is the “Wheel of Fortune,” whereby one’s circumstances change all of a sudden, seemingly with no rhyme or reason. It was a favorite image of the Middle Ages:

Notice that this shows exactly what Dylan is singing about. Fortune’s wheel was described most memorably by Boethius in his Consolation of Philosophy, which may be where Dylan came across it. But it’s also used as a picture (literally) at the beginning of Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens, and that could be his intermediary. Or, given its widespread use, he could have encountered it in any number of other places.

His use of it here wasn’t his first, however.

About a decade earlier, in the title track off of The Times They Are A-Changin’, Dylan had sung:

Come writers and critics

Who prophesize with your pen

And keep your eyes wide

The chance won’t come again

And don’t speak too soon

For the wheel’s still in spin

And there’s no tellin’ who that it’s namin’

For the loser now will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin’

“[D]on’t speak too soon” lest that idiot wind blow out of your unguarded mouth, I guess. It’s an idea that would be echoed later in “Foot of Pride” (if you haven’t heard Lou Reed’s version, stop what you’re doing and listen to it now.) Here’s the opening verse (and notice the “lion” in a possible echo of “Tangled”)[1]:

Like the lion tears the flesh off of a man

So can a woman who passes herself off as a male

They sang “Danny Boy” at his funeral and the Lord’s Prayer

Preacher talking ’bout Christ betrayed

It’s like the earth just opened and swallowed him up

He reached too high, was thrown back to the ground

You know what they say about bein’ nice to the right people on the way up

Sooner or later you gonna meet them comin’ down

Now on to the second. “Shelter from the Storm” is a song full of biblical imagery, and the singer explicitly compares himself to Christ a couple of times. One of those is in the fifth verse:

Suddenly I turned around and she was standin’ there

With silver bracelets on her wrists and flowers in her hair

She walked up to me so gracefully and took my crown of thorns

“Come in,” she said, “I’ll give you shelter from the storm”

Dylan would come back to a very similar use of this image in another love song, “When the Deal Goes Down” (Modern Times, 2006).

We eat and we drink, we feel and we think

Far down the street we stray

I laugh and I cry and I’m haunted by

Things I never meant nor wished to say

The midnight rain follows the train

We all wear the same thorny crown

Soul to soul, our shadows roll

And I’ll be with you when the deal goes down

It would be worthwhile, I think, to put these two songs in conversation with each other, though I’m not going to do that here. Suffice it to say at present that the evocative and complex texture of Dylan’s lyricism comes not just through the way he links his words to those of various literary traditions, but also through the way he links them to each other.

If this is right, then it means that his lyrics should be read and studied as a work or corpus as such, with its own inner coherence, and not just as a set of disparate pieces strung together haphazardly. Instead, the critic should see them as having their own self-contained integrity, like the works of Shakespeare or the poems of Vergil.

But, whether you buy this or not, take a moment to listen to Blood on the Tracks, especially if you never have. I think that you won’t regret it.

References

| ↑1 | Maybe not, though: Dylan has lots of lions. See “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie”; “Tough Mama”; “Golden Loom”; “No Time to Think”; and “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey Through Dark Heat).” |

|---|