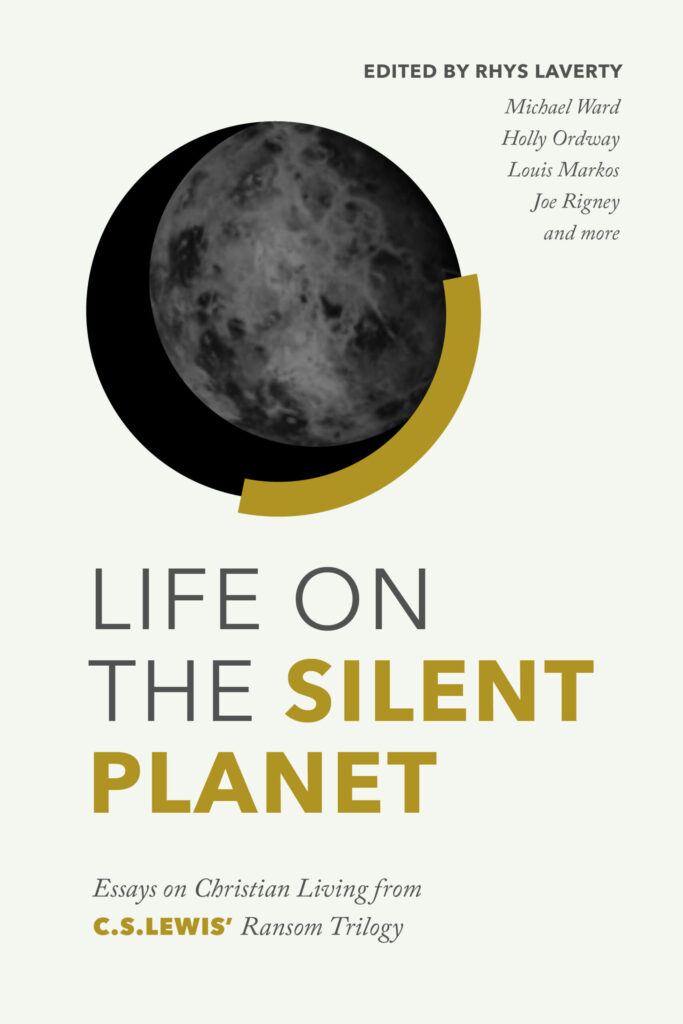

This article is a republication of the introduction to Life on the Silent Planet: Essays on Christian Living from C.S. Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy, published November 14th 2024.

Order here.

Growing up, I encountered three different C. S. Lewises. First, there was Lewis the Children’s Author. I inherited a box set of The Chronicles of Narnia from my brother, which I still have, and enjoyed them as much as the next child. Second, once I had been converted into the world of British evangelicalism, I encountered Lewis the Apologist. After coming to faith at the age of 12, I swiftly read Mere Christianity, and it soon became obvious that Lewis was ubiquitous in evangelical preaching via a few oft-repeated quotations, sermon illustrations, and book recommendations. Third, once I reached university to study English, I encountered Lewis the Literary Scholar. In all honesty, it was odd to realize that Lewis had a day job and wasn’t a full-time Christian apologist, but I supposed that a man had to earn a living—and I was soon glad to have him on my side in the critical theory maelstrom that my English degree turned out to be.

It took me, however, the best part of a decade to realize that there was, in fact, a fourth Lewis—one conspicuously absent from the writing and preaching to which I was accustomed. Evangelical Christians have heard countless preachers say that Jesus is “not safe, but he’s good”; we are used to (justified) rebukes for being “far too easily pleased.” My life was awash with The Screwtape Letters, The Problem of Pain, and Surprised by Joy, and even the occasional nod to something like Letters to Malcolm or A Grief Observed. Pretentious young humanities student that I was, I was confident during early adulthood that heaping praise on The Horse and His Boy and having The Great Divorce as my favorite was enough to mark me out as a Lewis aficionado among the hoi polloi.

And then I entered a different orbit, a different sphere of influence. I fell in with a different crowd—many of whom, I am glad and humbled to say, have contributed to the volume you hold now in your hands. As I drifted into the circles of the Davenant Institute—from purchaser of its books, to volunteer editor, to student, and eventually to staff member—I heard Lewis everywhere, yet in a different key. The go-to references here were not to Narnia or Screwtape or mud pies. The talk was all of men without chests, of eldila, of the medieval cosmos. I was able to dimly connect some of this to memories of watching Michael Ward’s documentary The Narnia Code when it was broadcast on the BBC in 2009, but I felt like an Englishman listening to the Dutch, picking out isolated familiar words but all the more disoriented for it. This was a whole dialect of Lewis-talk hitherto unknown.

Here emerged the fourth Lewis—what I have elsewhere called “Lewis the Prophet.”[1] Principally, this is the Lewis of The Abolition of Man and the Ransom Trilogy (or, if you prefer, the Cosmic Trilogy, but never, no never, the Space Trilogy). In these texts, with greater depth and in a more explicit fashion than anywhere else, Lewis locks horns with the challenges and evils of modernity, both identifying their influence in his own day and predicting how they would develop in the future.

In reality, there are not hard lines to be drawn between these various personae. Lewis shifts between them within the same work, even within the same paragraph, and sometimes they are indistinguishable. I am not wed to this fourfold office of Lewis. It is by no means perfect.[2] As the Apologist, he necessarily engages modernity and its apparent challenges to religious belief, and this work is something he does as a self-consciously modern man.[3] Elsewhere, in his children’s fiction, Lewis clearly has modernity in the crosshairs: any mention of schools in the Narnia books is as much an evisceration of modern education as anything in The Abolition of Man. The fact is that those first three strands of Lewis’s identity—Children’s Author, Apologist, Literary Scholar—are almost always entwined with one another at any given moment and were, I suspect, largely indistinguishable to Lewis himself. To weave tales that connected the truths of Spenser to Greek myth to the gospel and served to fortify a believer’s mind against the alluring sophistry of materialism—such a thing was for Lewis an almost reflexive act with a singular integrity, even if we could later logically distinguish the various elements.

It may in fact be that, rather than simply being a fourth strand among many, Lewis’s status as a “Prophet” is either the sum greater than all the parts, or simply what he is at a more basic level. Certainly, part of the reason that his legacy has endured since his death over sixty years ago is that he was a man peculiarly gifted and providentially placed in the pivotal moment of the first half of the twentieth century. His intellect was truly brilliant—a fact insufficiently appreciated by his popular audience, and willfully overlooked by scholars precisely because he has a popular audience. Further, he was born long enough ago that it was still possible for a solidly middle class boy from Ulster to receive a thorough education that incorporated enforced study of classical languages alongside vast swathes of unsupervised free time in which to read mountains of classical literature, and yet born recently enough to be, as we have noted, a native modern in his patterns of thought.

A Prophet Obscured?

Why, then, was Lewis the Prophet seemingly hidden from view during my younger years? Why was it a matter of course to take me through the wardrobe and caution me about Screwtape but not to tell me how to spot a man without a chest?

Selective Memory?

Perhaps, like so many evangelicals who gripe about aspects of their upbringing, my memory has become selective. Maybe The Abolition of Man was being quoted regularly and I just did not have ears to hear. Certainly, I have been surprised to find out that certain older saints from my past are fans of the Ransom Trilogy. One former church elder told me that, years ago, he had read one morning the passage in Perelandra in which Ransom discovers that the Un-man has been eviscerating frogs; that afternoon, he paid a visit to a mentally troubled church member who confessed she had been having visions of killing her dog. If you’ve ever been skeptical of the idea that reading fiction can have a payoff in pastoral ministry, perhaps this anecdote has disabused you.

Adult Content

It is also possible that the Ransom Trilogy appears somewhat neglected, at least compared to Narnia, because it is not a children’s book. Pastors and writers can often assume with an evangelical audience that most people will have some familiarity with Narnia from their childhood and so are likely quicker to draw on it for sermon illustrations and suchlike. This is not the case with the Ransom Trilogy however, since it was written for adults, and so is perhaps assumed to be less useful for teaching and discussion.[4]

A Question of Genre

Another reason for the neglect of the Ransom Trilogy specifically is simply the matter of genre. While science fiction is more popular than ever, it has moved on a great deal from the days of the genre’s father, H. G. Wells. Wells’s style can seem quaint, pulpy, and a little dull today—unsurprising, since his two most famous works, The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, were published in the late 1800s. Wells’s name conjures images of inelegant spacecraft made of pig iron, clean-shaven white male protagonists in Edwardian suits, and prose that could be read aloud in the tones of an over-earnest newsreader from the earliest days of broadcasting. By contrast, science fiction today is an ever sprawling playground for high concept storytelling, moral gray areas, and queer sexuality.

Despite being engaged in what has been called a “war of the worldviews” with Wells,[5] Lewis became an unashamed lover of “scientifiction” and a lifelong fan of Wells after first encountering his books at school.[6] Indeed, he regarded himself as an early enthusiast, long before “a bulge in production of such stories” began,[7] and Out of the Silent Planet contains a prefatory note refuting any suggestions that Lewis was “too stupid to have enjoyed Mr. H. G. Wells’s fantasies or too ungrateful to acknowledge his debt to them.”[8] The novel came out of an agreement Lewis made with J. R. R. Tolkien that they would each try to write the kind of stories they both enjoyed reading—time-travel for Tolkien, science fiction for Lewis.[9] Tolkien’s effort never saw the light of day during his lifetime, but Lewis produced what became the first novel in the Ransom Trilogy. The book has a self-consciously Wellsian feel, and it is precisely this Wellsian feel that I think leads many today to avoid picking the novel up in the first place. Whereas works of fantasy (a genre which, like science fiction, is more popular now than it has ever been) remain relatively timeless, any science fiction produced prior to the Golden Age of Science Fiction in the 1930s and 40s (and, increasingly it seems to be, anything produced prior to the 1980s) is effectively regarded these days as “proto-science fiction” and so as less amenable to our twenty-first century sensibilities. As you will imagine, since I am editing a book of essays on the trilogy, I regard this as a great shame in its own right, but doubly so given that Perelandra and That Hideous Strength are each of a totally different genre from their predecessor.[10]

Needless Obscurity?

Lewis the Prophet has also surely been given short shrift because his most “prophetic” texts (that is, the Ransom Trilogy and Abolition) are by no means his most accessible. Despite its brevity, Abolition is a work so dense that it has entered the elite circle of books that have spawned their own commentaries.[11] As Michael Ward notes, Lewis himself believed that the book had sold poorly, and his friend and biographer George Sayer attributed this in part to its inaccessibility.[12] Yet Ward points out that Abolition actually sold well for a volume of academic philosophy, was reviewed well upon release, and

has gone on to establish a reputation as a genuine and seminal classic. It has proved to be influential with a large and diverse readership—philosophers, educators, literary critics, intellectual historians, jurists, atheists, agnostics, people of faith—and is now generously (though of course not unanimously) considered among his most perceptive, penetrating, and important pieces of writing.[13]

Plenty, then, honored Lewis the Prophet in his hometown upon publication and have continued to pay heed to him since. Yet it seems reasonable to assume that whatever audience helped to make Abolition a solid seller in its day were still the beneficiaries of a general education—or at least a cultural milieu—that allowed them to keep up with Lewis (and even back then, such educations were on the decline, this being the whole point of Abolition). In the decades since, such an education has become almost solely the reserve of the highest elite—the philosophers and such who, Ward notes, acknowledge their debt to Abolition. And even today’s elites are lucky if they get schooled in the most basic classical and medieval references.[14] Ward references John Lucas, Alan Jacobs, A. N. Wilson, Tony Nuttall, Mary Midgley, Mark Souder, Leon Kass, Joseph Ratzinger, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Francis Fukuyama, and Wendell Berry as among those who have praised Abolition. The youngest of these was born in 1958. Anyone born and educated since then, elite or not, has faced an uphill struggle to be able to enter Lewis’s thought-world.

Much the same can be said of the Ransom Trilogy. Lewis’s semi-fictional world draws on, alludes to, and even outright incorporates elements from an innumerable array of philosophical and literary sources ranging from Plato to Arthuriana to H. G. Wells. As such, there has arguably been an ever-growing barrier to entry if readers are to appreciate and enjoy the series. Certainly, many have enjoyed the books over the years knowing little to nothing about Lewis’s sources. Lewis, with his penchant for atmosphere, or “Donegality,” possesses a marked ability to write books that are in incredibly close dialogue with other texts and yet stand entirely on their own two feet.[15] The Great Divorce was my favorite Lewis work long before I knew anything about Dante, and the general public enjoyed the Chronicles of Narnia for decades before Michael Ward cracked the Narnia Code.[16] Yet the Ransom Trilogy places its allusions and references somewhat closer to the surface than either of these, and so perhaps requires something more of a “working knowledge” to be entered into. The series may still have been relatively accessible in its day, but ironically it has become less so in ours precisely due to the modern ills about which it warns us.[17] It is not so much that the barrier to entry has become higher over time; rather we, having received educations that were neither scientific nor classical but simply “modern,” have sunk lower and lower.

Pietism

The final—and I suspect, major—reason that evangelicals have overlooked Abolition and the Ransom Trilogy is because of our tendency toward pietism. David Bebbington famously listed evangelicalism’s four defining features as biblicism, crucicentrism, conversionism, and activism.[18] Together, the combination of all four tends toward a form of pietism, by which I mean a fairly narrow focus on individual salvation and godliness.

With this in mind it is easy to see why Lewis the Children’s Author and Lewis the Apologist have been so popular with evangelicals, despite Lewis being no evangelical himself and being first regarded by the constituency as “a smoker, a drinker, and a liberal”[19] (and even accidentally as a Roman Catholic!)[20] when his works arrived in the USA. His straightforwardly apologetical works, aimed principally at non-believers, such as The Problem of Pain, Mere Christianity, and Miracles, push readers, to varying degrees, toward conversion to the crucicentric Christian faith, or at the very least toward the same preliminary “mere theism” to which Lewis famously became the most reluctant convert before fully embracing Christianity. The Narnia books can do much the same, smuggling in apologetics under the guise of narrative. Absorbing quotations and arguments from these works, or even just giving the works to unbelievers as gifts, has long been part of evangelical activism.

Furthermore, works such as The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, A Grief Observed, and Letters to Malcolm, along with the Chronicles of Narnia, have fairly obvious and immediate applications to personal devotion to Christ. In particular, the character of Aslan has always played well to evangelical emphases: his trustworthy signs for Jill Pole resonate with biblicism; his death at the Stone Table with crucicentrism; his undragoning of Eustace Scrubb with conversionism; his ability to inspire the embattled Old Narnians with activism. Screwtape remains an immensely practical work of spirituality, and it is perhaps telling that it is this work more than any others that opened a door for Lewis with evangelical readers.

By contrast, Abolition and the Ransom Trilogy do not seem as directly concerned with questions of apologetics or personal piety (note, I do emphasize the “seem” here). Certainly, parts of the trilogy are quite obviously applicable to conversionism and activism.[21] But for the most part, tracing lines from the Ransom books to contemporary Christian living requires more effort and reflection than doing so from Narnia. One way to illustrate this point is simply to note that Maleldil is simply not as present in the Ransom Trilogy in the same way that Aslan is in the Chronicles of Narnia. If Lewis shows something of his hand regarding the motivation behind the Narnia Chronicles when Aslan says he drew Eustace and the Pevensies into Narnia that they might “know him better” by “a different name” in their own world, he does not seem to be holding similar cards when penning the Ransom books.

Similarly, the Ransom books are undoubtedly an apologetical project in the same vein as Narnia, stealing past watchful dragons with fictionalized Christian truth.[22] Yet the form and structure of the trilogy does not lend itself to quotable references or images fit for sermons or quickfire apologetic debates in the same way that other Lewis works do. Lewis is undoubtedly aiming at what we would today call a “reenchantment” for modern readers in the Ransom Trilogy, but it is as if it comes about by way of a very long incantation that cannot be interrupted without having to start again.

The Ransom Moment

This latter point on pietism brings us squarely to the purpose of this essay collection. The shared conviction of this volume’s contributors is that it has been a profound mistake to think that the Ransom Trilogy lacks immediate relevance to the Christian life, and that it is time for this to change.

For one thing, the trilogy overlaps far more than is often thought with some of Lewis’s most practical works. Take Perelandra for instance: the novel is largely taken up with Ransom being face to face with the Devil himself while trying to prevent the Green Lady, the Eve of Venus, from falling into sin. As such, it has more than one or two things in common with The Screwtape Letters.[23]

For another (and this is the more substantial point), while the trilogy’s principle concerns may seem quite removed from the Christian life, as we move further into the twenty-first century, it is becoming increasingly clear that they are in fact matters of utmost urgency and practical import for orthodox Christian believers. Christians of all stripes do not see this because, all too often, we have made our peace with the modern ills that Lewis is trying to highlight—and evangelicals do so to the detriment of the personal piety with which they are supposedly so concerned.

By way of example, consider two of the Ransom Trilogy’s most prominent (and strongly related) themes: technology and gender. At the macro-level, our politics today is increasingly dominated by both a technocracy that sees technological innovation (including transhumanism) as the solution to all civilizational ills, and by an ideological rejection of the natural givenness of sex and gender that has reached its most extreme manifestation in an embrace of transgenderism but that was at work long before then. At the micro-level, our daily lives are increasingly frayed at the edges by the addictive yet alienating tug of screens and haunted by the directionlessness of men and women who struggle to know what on earth being either of those things actually means.

The damage wrought by this current zeitgeist around technology and gender is becoming more and more evident. And it is for this reason that we find ourselves in a “moment” in which the Ransom Trilogy has truly come into its own. Upon first discovering the trilogy a few years ago, I was simply floored on page after page after page by its prescience and scandalized that no one had thrust it into my hands with urgency sooner. One could scarcely have designed a more retroactively prophetic set of novels for our day if they had tried. The unashamed aim of Life on the Silent Planet is to bring Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy into popular discussion about Christian living such that it gains its rightful place as the equal of the Chronicles of Narnia and Lewis’s most famous Christian nonfiction.

It is worth saying at the outset that the relevance of the essays for Christian living is not to simply argue that for Christians to survive and thrive in modernity, they must turn back the clock. Lewis himself knew that we can never “go back” and “unmodernize” ourselves. Some kind of massive future technological collapse aside (a possibility not to be discounted), modernity happened, and there’s nothing we can do about it. We’re all Moderns now. Our felt experience of the world is a million miles away from that of the Medievals who so fascinated Lewis. We noted technology and gender as two particular challenges above, but of these two, technology is the more fundamental. It profoundly warps the way in which we inhabit the world. When it comes to the existence of God, for instance, my colleague and fellow contributor Joseph Minich explains that, in the modern world, “whatever one believes propositionally about the question of God, God’s existence is not felt to be obvious in the same way that, for instance, the fact that you are reading this right now feels obvious.”[24] Minich roots much of this sense of divine absence in the alienation caused by what he calls “modern technoculture.”[25] A creation in which technology dominates so much, especially our daily labor, cannot help but feel radically different from what came before—to the extent that even the Creator himself grows strangely dim to us.

Much the same can be said of the reality of sex and gender difference. When embroiled in gender debates, Christians far too often begin the discussion with the explosion of feminism in the 1950s and ‘60s and assume that modern gender confusion simply arises from ideology. But Lewis wrote Jane Studdock in the early ‘40s, and he died in 1963, the year that, according to Philip Larkin, sexual intercourse began. The great gender crackup, then, clearly goes back further than the middle year of the twentieth century and arises from more than mere ideology. Increasingly, Christian thinkers are casting their minds further back to the technological innovations of the Industrial Revolution as the true starting point for our modern gender wars. Our ideological ructions have largely been downstream of this and are unimaginable without certain technologies underpinning them.[26]

Although reconceiving our modern problems this way is more accurate, it can at first be a great deal more depressing. If the reality of technological innovation means that we cannot reverse the clock, that we cannot make things such as God’s existence or the goodness of gender difference intuitive in the way that they once were, then why bother? We can see immediately why it is so tempting to believe this is all a matter of ideology, since we can always either tantalize ourselves with the possibility that we will win the battle of ideas, or savor the self-righteousness in the long defeat of martyrdom when we don’t. Most contemporary Christians, however, do simply admit defeat, absorbing to varying degrees the prevailing modern consensus on technocracy and gender and finding ways to whitewash it with respectable religious language. Evangelicals in particular do this with one well-intentioned but profoundly misguided eye on evangelism: to the men without chests, we become men without chests.

The fruitful path for modern Christians that Lewis imagines, however, is different. It is neither tilting at windmills in some endless ideological conflict between “liberalism” and “conservatism,” nor is it a weak-kneed embrace of the modern status quo. To put it crudely, when confronting the ills of modernity, the Ransom Trilogy suggests something like “the only way out is through.” This does not mean a teeth-gritting charge through with our heads down, as if modernity isn’t happening and as if it doesn’t have some genuine benefits. No; we will all be—and have already been—changed. Joseph Minich has described modernity as “the simultaneous global renegotiation of all human custom”—a remarkably accurate definition I think, but it can be one that causes us to throw up our hands again.[27] What hope have we of coming back from a point where all human existence has become negotiable? But the Tao, which Lewis defines and defends so expertly in The Abolition of Man, is such that it will out in the end, and it is possible to have passed through the gauntlet of modernity—indeed, to still be living within it—and to sincerely reembrace, in our own way, those things that our ancestors did not have to think twice about. Indeed, if the Tao is real, this simply must be the case. It is particularly helpful here to remember that one of Lewis’s other names for the Tao is “The Way”: “It is the Way in which the universe goes on, the Way in which things everlastingly emerge, stilly and tranquilly into space and time. It is also the Way which every man should tread in imitation of that supercosmic progression, conforming all activities to that great exemplar.”[28] Without doubt, hard-nosed opposition to and rejection of much of the modern project is called for, and Lewis knew this. “Ethics, theology, and politics” are all at stake when the Tao is forgotten, and so political solutions can and should be sought.[29] And yet Lewis seems resolutely, insouciantly convinced that it is possible for us to be, in some sense, modern men, women, and Christians who are nevertheless in step with the Tao—and indeed, we could perhaps even read him in places as seeing a kind of felix culpa in modernity, as something intended ultimately for man’s good by divine providence. We may live on Thulcandra, the silent planet—our fallen home, out of tune with the intended music of creation—and perhaps, in the modern era, with its rejection of the very idea of such a thing as the Tao, the silence has become particularly deafening. And yet we know that Maleldil has “taken strange counsel and dared terrible things, wrestling with the Bent One in Thulcandra,” and so life on the silent planet is always, for the Christian, possible.[30]

Summary of Chapters

Our volume dedicates three chapters each to Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra, and six to That Hideous Strength. This disparity is a proportionate one, since the third novel is longer than the previous two put together.[31] We begin with renowned Lewis scholar Dr. Louis Markos’s chapter “Which Way, Weston Man? Good, Evil, and Cosmological Models in Out of the Silent Planet.” From the outset, I wanted this book to begin with a chapter that made clear the importance of Lewis’s reappropriation of the medieval cosmos for the trilogy, since this is the backdrop against which the drama of the whole series is staged. It is the sine qua non, and Dr. Markos provides a stellar account of why this is the case. In the second chapter, “The Education of Dr. Ransom: First Steps from Pedestrian to Pendragon,” Joe Rigney considers the transformation we begin to see in the trilogy’s titular protagonist as he finds himself transported to Malacandra. Ransom’s chief vice at the outset, Dr. Rigney argues convincingly, is the passion of fear—something that he begins to overcome only as he uncovers the true order of the cosmos. Colin Smothers then surveys the vital theme of masculinity in our third chapter, “Men Are From Mars: Masculinity in Out of the Silent Planet,” zeroing in particularly on how Lewis shows us masculinity in courage, responsible fatherhood, and self-sacrifice.

In our first Perelandra chapter, “Enjoyment and Contemplation: The Green Lady, Self-Knowledge, and Growth in Maturity,” Christiana Hale pairs the novel with Lewis’s essay “Meditation in a Toolshed,” beautifully applying Lewis’s categories of “enjoyment” and “contemplation” to the Christian life in service of true humility and true obedience. In the next chapter, Bethel McGrew grapples with the Screwtapery of Perelandra in “The Devil Went Down to Venus: Lessons from the Un-man,” considering in particular the thorny question of how we can possibly love enemies who are so deeply in thrall to the Bent One. In the final chapter of this section, “A Taste of Paradise: Naming, Restraining, and Embracing Pleasure on Perelandra,” my own contribution, I take a close look at how Lewis portrays unfallen sensual pleasure on Perelandra and what it can teach us about the highs and lows of pleasure here and now.

Our third section begins with Dr. Michael Ward’s chapter “Selling the Well and the Wood: That Hideous Strength and the Abolition of Matrimony.” This chapter expands on a 2022 First Things article by Dr. Ward entitled “C. S. Lewis and Contraception,” making a provocative but thoroughly convincing case for That Hideous Strength being a sustained critique of the use of contraceptive technology.[32] Then, in “Lewis’s Apocalypse and Ours,” Dr. Joseph Minich considers how Lewis’s “apocalyptic” vision of modernity compares to recent attitudes toward the End Times among some evangelicals, and how it can help to reorient us within the culture wars, particularly when it comes to gender. Next, in his chapter “The Untabled Law of Nature,” Colin Redemer makes a compelling argument that That Hideous Strength portrays modern men not simply as lacking chests but as lacking another important, and distinctly male, body part—one that we sorely need to regrow if we are to compete for the Tao. In “Arthur in Edgestow,” Dr. Holly Ordway takes on the daunting task not only of making sense of what on earth Lewis is doing with the Arthurian elements of his novel, but what their relevance could possibly be for the Christian life (and she succeeds with characteristic aplomb). In the penultimate chapter, “The Problem of Jane,” Susannah Black-Roberts tackles the supposed boogeyman (or perhaps, boogeywoman) of Lewis’s attitude to women’s sexuality, skewering misplaced feminist critiques and revealing that the so-called problem of Jane ultimately has nothing to do with sex, or women, at all. Finally, Jake Meador concludes our collection with “Bureaucratic Speech in That Hideous Strength,” attempting the impossible task of making sense of the NICE’s internal conversations and ably pointing out how Lewis’s satirical diagnosis of obfuscatory modern speech is as relevant now as it was then.

It has been a true privilege to have worked with the contributors for this volume, and I am grateful to them all for their hard work, research, and willing collaboration during the editorial process. These chapters have, I believe, broken genuinely new ground, either by unearthing insights and connections hitherto unseen or by finally providing long overdue go-to surveys of particular themes or topics in the Ransom Trilogy. All of them, even those more scholarly ones, have remained firmly on-task in applying Lewis’s work to the topic of Christian living.

I am especially glad to have brought together established Lewis scholars with friends and colleagues from the Davenant Institute and its network. I myself am entirely indebted to this latter group for plunging me head first into the world of the Ransom Trilogy, and made it my mission in part to bring their appreciation for these novels—as practical as it is scholarly—to a wider audience. In part, I hope for that wider audience to consist of Lewis scholars; mostly, however, I hope that it will consist of Christian laypeople and pastors who are willing to let these books work their way into areas of their Christian lives that may otherwise have gone unexamined. That, certainly, is what these books have done for me.

Here on the silent planet, we are out of tune with the music of the spheres, out of step with what Perelandra calls the Great Dance. But, in Maleldil’s grace, the music plays on, and we are invited out of the silence and into the dance. He who has ears to hear, let him hear.

Order Life on the Silent Planet today!

With Michael Ward, Holly Ordway, Louis Markos + more!

“This book opened up the Ransom Trilogy to me like no other. If you only read one book on Lewis this year, read this one“

– Joel Heck, Concordia Theological Seminary

See my article “Lewis the Prophet,” The Critic, November 2023, https://thecritic.co.uk/issues/november–2023/lewis-the-prophet/. It was only after writing this piece that I found that I am in good company in referring to Lewis as a prophet, with Lewis scholars such as Michael Ward and Malcolm Guite describing The Abolition of Man as displaying Lewis’s “prophetic mode.” ↑

Till We Have Faces, for instance, as Lewis’s latest and perhaps greatest achievement (during his lifetime anyway), arguably does not fit entirely well within the framework. ↑

For an exploration of Lewis’s self-conscious status as a modern man evangelizing other modern men, see my colleague and fellow contributor Joseph Minich’s lecture “C. S. Lewis as Sage of Modernity,” YouTube, January 21, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MhG0I-EwAso. ↑

I am grateful to John Barach for making this point. ↑

See Brenton Dickieson, “The War of the Worldviews: H. G. Wells vs. C. S. Lewis (Part 1),” A Pilgrim in Narnia, August 28 2012, https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2012/08/28/warofworldviews1/. ↑

C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy (London: Collins, 2012), 38. ↑

C. S. Lewis, “On Science Fiction,” in Of Other Worlds (London: HarperOne, London, 2017), 93. ↑

C. S. Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet (London: HarperCollins, 2005), vii. ↑

Tolkien recounts this story in his letter to Christopher Bretherton, dated July 16, 1964, in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, rev. ed., ed. Humphrey Carpenter with Christopher Tolkien (London: Harper Collins, 2023), 487. ↑

I am of the opinion that Out of the Silent Planet is one of two or three (maybe four) novels Lewis ever wrote. Most of his fictional works are other things disguised as novels. ↑

I am referring to Michael Ward’s After Humanity: A Guide to C. S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man (Park Ridge: Word on Fire Academic, 2021). ↑

Ward, After Humanity, 1. ↑

Ward, After Humanity, 2. ↑

As mentioned, I spent my undergraduate years at the University of Exeter (2011–2014), a member of the Russell Group (the British equivalent of the Ivy League) being schooled in critical theory, and it took me a few years into graduate life to realize I had not actually been taught anything about literature. And this was a decade ago, before we reached the critical theory inflection point of more recent years, when the ideas swirling around my undergrad lecture halls spilled out into the mainstream. ↑

Lewis refers to the “Donegality” of Donegal in Spenser’s Images of Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), 115. Michael Ward effectively coined it as a phrase in Lewis studies in his Planet Narnia. ↑

See Michael Ward, Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C. S. Lewis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010). I am aware that some still question the overall thesis of Ward’s book, but quite frankly I find opposition to it baffling and have yet to read an attempted refutation of it, scholarly or otherwise, which is anything approaching convincing. ↑

It might be suggested that Lewis had simply not yet honed his craft as well as he would later on with Narnia, or that he had not learned the kind of restraint needed to write things that were richly allusive and yet still accessible. I am unconvinced by this however. By 1943, the same year that Abolition was published and That Hideous Strength was drafted, Lewis had acknowledged that his first work of fiction, The Pilgrim’s Regress, suffered from “needless obscurity” (“Preface to the Third Edition” in The Pilgrim’s Regress [London: Fount, 1977], 9). He also began writing the elegant The Great Divorce in 1944, while finishing off That Hideous Strength. So it seems that, by the time Lewis was writing both the Ransom Trilogy (certainly the third novel, at any rate) and his Abolition lectures, he was well aware of the dangers of needless obscurity and was more than capable of hiding his influences in plain sight if he wanted to. Perhaps he chose at times to engage in some “needful obscurity” as he felt led, but it seems unjustified to view obscurity as a major vice for him by the time he hit his literary stride during the war years. ↑

David W. Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (London: Routledge, 1989), 2–3. ↑

Quoted in Stewart Goetz, A Philosophical Walking Tour with C. S. Lewis: Why It Did Not Include Rome (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 6. ↑

Mark Noll, C. S. Lewis in America (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2023), 106. ↑

See Gavin Ortlund, “Conversion in C. S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength,” Themelios 41, no. 1 (April 2016), https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/article/conversion-in-c-s-lewis-that-hideous-strength/. ↑

The image of “stealing past watchful dragons” is used by Lewis to describe precisely this in his essay “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to Be Said,” in On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature (London: HarperOne, 2017), 70. ↑

Indeed, as Brenton Dickieson discovered in 2015, Lewis’s original prologue to The Screwtape Letters presented them as a set of fictional correspondence that had fallen into the hands not of an unnamed editor, but of Dr. Ransom himself. See Brenton Dickieson, “A Cosmic Find in The Screwtape Letters,” October 28, 2015, https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2015/10/28/a-cosmic-find/. ↑

Joseph Minich, Bulwarks of Unbelief: Atheism and Divine Absence in a Secular Age (Bellingham: Lexham Academic, 2023), 5. ↑

Minich, Bulwarks of Unbelief, 6. ↑

A seminal text in this regard is Ivan Illich’s 1982 book Gender, which has been gaining currency among Christian thinkers in recent years. I am particularly indebted to the labors of my friend and colleague Alastair Roberts in this area (he is also the husband of one of our contributors). ↑

Joseph Minich, “A Very Nuanced Take on Everything,” Ad Fontes, June 11, 2022, https://adfontesjournal.com/pilgrim-faith/a-very-nuanced-take-on-everything/. ↑

Lewis, The Abolition of Man, 28. Emphasis added. ↑

Lewis, The Abolition of Man, 16. ↑

Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet, 154. ↑

I am grateful to fellow contributor Joe Rigney for making this suggestion at the outset of the project. ↑

Michael Ward, “C. S. Lewis and Contraception,” First Things, November 3, 2022, https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2022/11/c-s-lewis-and-contraception. ↑